Japanese Food History and Culture

Shochu: Distilled Liquors in Japan

Distilled liquors are very popular in Japan nowadays. Shōchū (焼酎, burned alcohol) is a mainstay at bars, taverns, and restaurants, and its versatility means there is a wide and varied offer available to the alcohol amateur. As for a lot of Japanese foods and drinks, the history of distillation in Japan is linked to the history of its overseas and inland trade. In this article, we will look at the development of the domestic production of distilled liquors leading to today’s popular shōchū.

The historical part of this article is mainly based on research compiled in the book Nihon no Sake no Rekishi (日本の酒の歴史) by Katō Benzaburō. Other sources will be referred to as usual.

Introduction of distilled liquors to Japan

How and when distillation techniques were introduced to Japan is not entirely clear. They seem to have appeared in China around the 14th-15th century, possibly from Thailand. In the 14th century, a network of trade, tribute relations, and occasional piracy was linking Southeast Asia, Korea, the Ryūkyū kingdom (current day Okinawa), and Western Japan. This network, centered around Hakata in Echizen province, was probably the way distilled liquors were introduced to Japan.

The most widely accepted theory is that distilled alcohol was traded via Korea to the Ryūkyū islands, where a local variety called awamori (泡盛) is produced, before making its way to the mainland through the Satsuma domain in southern Kyūshū. Several mentions of alcohol being traded or sent as a tribute can be found in Korean and Japanese records from the 15th and 16th centuries, but there is no clear evidence those were distilled liquors.

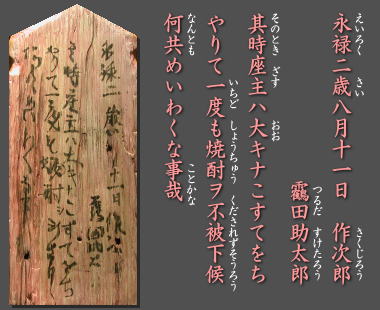

The oldest known use of the “shōchū” characters was found at the Kōriyama Hachiman sanctuary in Kagoshima prefecture. Two carpenters who participated in the construction of the sanctuary engraved a block of wood, where they complained about the head of the sanctuary being a pinch-purse and not even serving them a flask of shōchū. The engraving, dated to 1559, means that by the mid-16th century there probably was already a shōchū industry in Japan.

Inscription found at the Koriyama Hachiman sanctuary. The shochu characters can be seen in the 4th column from the right. © Wikimedia Commons

Woodblock print of Asano Naganori assaulting Kira Yoshinaka in the Pine Grand Corridor. © Wikimedia Commons

Distilled alcohols in the Edo period

Imported distilled liquors such as the Okinawan awamori and araki (from Arabic arak) were a rare and appreciated commodity. They were consumed for their taste, but also for their medicinal properties. Treaties from the Edo period mention that the consumption of shōchū can help with stomach aches, digestive troubles, and similar ailments.

Shōchū was also used to disinfect wounds. In 1701, the daimyō Asano Naganori of Akō domain (Harima province) attacked with a dagger the court official Kira Yoshinaka in the Pine Grand Corridor of the Edo castle, an event that would lead to the famous incident of the forty-seven rōnin, a popular story often portrayed in Japanese media. After the attack, the wound sustained by Kira was treated by a physician who is recorded as using warmed shōchū to clean and disinfect the cut.

Distillation process

A Japanese single still for shochu. © Wikimedia Commons

Distillation produces more concentrated alcoholic solutions compared to fermentation thanks to the lower boiling point of alcohol compared to water. An alcoholic beverage is cooked until the alcohol starts to evaporate. The alcohol vapor is then collected and condensed to produce the distilled solution. A distilled liquor can be kept longer than brewed alcohols, and its taste and properties are quite different from the original beverage.

A shōchū recipe from 1596 describes the base for the distillation process as kozake (濃酒), an alcohol made from rice and kōji mold, with kasu (糟 or 粕) sake lees mixed in. The resulting shōchū was called midori shōchū (みどり焼酎). Kasu is a by-product of sake production, obtained after filtration of the moromi (もろみ) fermented rice mash from which the sake is extracted. Being able to recycle a by-product that would otherwise be discarded as waste might also have contributed to the popularization of midori shōchū. To reduce the necessary work, moromi (already containing the alcohol and kasu) could be used as a base for distillation.

Starting around the end of the 17th century, shōchū began to be classified as moromitori shōchū (もろみ取焼酎) if distilled from moromi or kasutori shōchū (粕取焼酎) if distilled from kasu.

Although clear evidence is difficult to come by, it seems that various base ingredients were used for shōchū production as early as the Edo period. Other than rice, Satsuma imo, barley, millet, and chestnuts were also used. Kurozatō (黒砂糖) unrefined brown sugar, akin to molasse, was also a common base for both shōchū and awamori.

The pot stills used for shōchū production were called ranbiki (らんびき), from the Dutch alambigue (alembic). Probably imported or copied from Okinawa, Southeast Asia, or China, the first ranbiki used earthenware pots. At the end of the 17th century, other materials such as copper, glass, or porcelain appeared. Models made after Japanese designs used wood barrels and bamboo pipes.

Introduction of the column still and shōchū categories

In 1895, a continuous column still was imported from England. This new equipment allowed for a more efficient production process resulting in a high-purity product. This new type of shōchū produced with column stills became popular thanks to its lower price, higher purity, and the fact it could be made without using rice, an advantage during the rice shortages provoked by the wars of the 20th century.1

Under the Japanese taxation laws, shōchū produced with column stills is classified as kōrui shōchū (甲類焼酎) and shōchū produced with column stills as otsurui shōchū (乙類焼酎). The characters kō (甲) and otsu (乙), derived from the Chinese calendar, are used to enumerate lists, comparable to type A and B. However, they might convey a nuance of quality, kō being perceived as a higher grade than otsu, even though only the production method is considered. That is why recently some otsurui shōchū distilleries have been using the alternative appellation honkaku shōchū (本格焼酎). Kōrui and otsurui shōchū can also be blended to make konwa shōchū (混和焼酎).2

New kōji molds

The production of shōchū requires the use of kōji molds, also used to make sake, soy sauce, miso, and amazake. Nowadays, different types of kōji are available to makers depending on their needs, but this wasn’t always the case.

At the start of the 20th century, a Japanese researcher named Kawachi Genichirō working in southern Kyūshū realized that the yellow kōji (aspergillus oryzae) used to make sake in colder regions of Japan wasn’t suited to the hotter climate in the South. He worked on developing a strain that would be suitable for shōchū production in hot conditions and managed to produce in 1910 a variant of the black kōji (aspergillus luchuensis) already used in Okinawa to make awamori. This new mold, dubbed aspergillus luchuensis var. kawachii, allowed for an improved yield of shōchū across southern Kyūshū. In 1924, Kawachi developed a new strain from a mutation of the black kōji, dubbed white kōji (aspergillus luchuensis mut. kawachii). To this day, those different types of mold are used by shōchū producers depending on their environment, ingredients, and manufacturing processes.3

Kome koji. © Photo-AC

Kome koji. © Photo-AC

Shōchū nowadays

Shōchū is a very common drink in Japan, often found in supermarkets, convenience stores, and specialized shops. It is also served in restaurants, bars, and izakaya.

A wide variety of brands and ingredients is available. The most common bases are rice, barley, sweet potatoes, buckwheat, and brown sugar. Other bases include milk, chestnuts, sesame, kasu, shiso perilla leaves, kabocha, corn, carrots, and wakame seaweed.4

Shōchū is often served neat (undiluted) or on the rocks (mixed with ice). It can also be mixed with water, cold (mizuwari) or hot (oyuwari). The popular chūhai cocktail is made by mixing shōchū with citrus soda.

In Japan, shōchū is more widely consumed than the famous rice sake. Kyūshū has the highest consumption rate per capita in the country, especially in the southern prefectures. On the contrary, central Japan has the lowest consumption rate per capita, with sake being more popular around those parts.5