Japanese Food History and Culture

Kuri: the Japanese Chestnut – Part 1

When I was a kid growing up in Geneva, we would all get excited come winter, as it meant grilled chestnut stands would open, and we would pester our parents until we could get a handful of delicious, sweet marrons grillés wrapped in a brown paper bag. This love for the small fruit never left me, which is why I was delighted to discover that people in Japan share this passion, and that kuri (栗) can be found everywhere; I was exhilarated the day I found a giant size pack of chestnuts in a local supermarket! Often associated with the Satsuma imo and the kabocha, it is very popular. In today’s article, we will cover the history of this Japanese staple, predating even rice, as well as its evolution, cultivation, and famous dishes.

This is the first part of a two-part article about the Japanese chestnut. It covers the cultivation of the kuri from prehistoric times up to the Meiji period. The second part discusses the modern cultivation and consumption of the chestnut. Unless stated otherwise, the information shared in this article is based on the research compiled in the book Kuri – Mono to Ningen no Bunkashi (栗・ものと人間の文化史) by Imai Keijun. Other sources will be referred to as usual.

Prehistory: chestnut as a staple

Archaeological evidence shows that chestnuts have been consumed in Japan ever since humans settled the islands. During the Jōmon period, wet-field rice agriculture wasn’t yet known, and gathered nuts such as chestnuts, acorns and walnuts played an important role in the diet as staple foods. Chestnuts in particular have been found in archaeological sites of this period all across Japan except in Hokkaidō. Central Honshū has an especially high concentration of chestnut remains.

Kuri could be preserved during the winter, when food was more difficult to find, a role that would later be played by rice. They were probably ground into flour to be used in porridges or formed as dumplings.

Chestnut wood was also valuable as a construction material, thanks to its high tannin content making it especially resistant to water damage. It was used in buildings for structural pillars, pickets, and oars.

Although the matter is still debated today, paleoecology studies using pollen analysis seem to indicate that during the Jōmon period already some form of chestnut tree cultivation in orchards may have been practiced.

Following the introduction of wet-field rice cultivation from China at the end of the Jōmon period, chestnut and chestnut wood consumption took a backseat during the Yayoi period and the Kofun period.

Case of shin kuri new chestnuts.

Ancient age: chestnut harvest and tributes

Chestnut cultivation is attested in Nara period documents such as the Nihon Shoki (Chronicles of Japan), Fudoki (provincial reports on geography, culture, and resources), and Shōsōin Monjo (archives stored at the Tōdai-ji temple). This last document also mentions two methods for cooking kuri: hoshi guri (干栗), where the chestnut is steamed and then peeled, and kachi guri (搗栗), where it is dried before being peeled. Chestnuts are also mentioned as payment for taxes, like in the Izuminogen Shōzeichō (Register of Taxes of the Izumi Province, 738).

In the Heian period, further references can be found in the Engi Shiki (Procedures of the Engi Era, 927) in the list of tributes to the imperial court. Several types of kuri are mentioned, although the differences are not explained, so the following descriptions are only guesses:

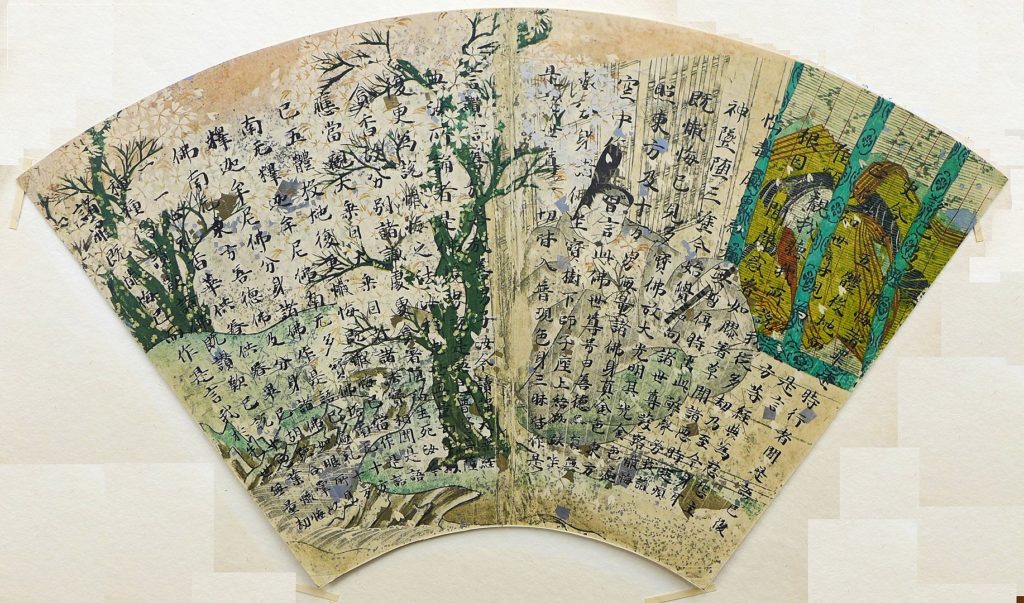

A fan from the Senmen Koshakyō. © Wikimedia Commons

Hira guri (平栗子): steamed, then ground or pounded, a preparation method found in later periods as uchi guri (打栗).

Ama guri (甘栗子): stone grilled and sweetened.

Kachi guri (搗栗子): already mentioned during the Nara period (see above).

Hira guri (扁栗子): another spelling for the previously mentioned hira guri?

Yute guri (楪栗子): boiled chestnut.

Kai kuri (削栗子): grated chestnut, or chestnut shavings.

The first known depiction of chestnut harvesting also dates back to the Heian period. The Senmen Koshakyō is a mid-12th century collection of paper fans on which Buddhist sutras have been written. In addition to their artistic and religious value, the backgrounds are illustrated with various paintings, showing interesting details about daily life at the time. One of those paintings depicts barefoot women in short-sleeved kimono gathering chestnuts on the ground by hand.1 Indeed, in contrast to other fruits, the kuri is harvested not while still on the tree, but once it has fully ripened and fallen from the branch. Interestingly, this method of picking up kuri by hand hasn’t changed much and is still practiced today.

In the Nara and Heian periods, selective breeding of shiba guri (柴栗) wild chestnuts, also called yama guri (山栗), progressively lead to varieties with bigger fruits and higher yields. Those efforts were centered around Tanba province, which became famous for the quality of its tanba guri (丹波栗).

Tanba guri

The tanba guri was also sometimes referred to as teteuchi guri (父打栗). The etymology of this term isn’t clear, and there are several competing explanations. Based on the chinese characters 父打栗 (father – hit – chestnut), a story goes that an upset kid threw one at his father in a fit. Another theory uses homophonic characters 手手打栗 (hand – hand – hit – chestnut) supposedly describing kids rejoicing and clapping in their hands at the sight of the big chestnuts. Yet another possible etymology would have tete be a deformation of temoto (“at hand”) as mispronounced by toddlers.

The development of the tanba guri is centered around the Settan region, a mountainous area of Tanba province with numerous temples and imperial grounds. The lack of land favorable to rice cultivation led to chestnuts being used as an alternative to rice for paying land taxes. Those taxes were measured by volume, leading producers to selectively breed bigger chestnuts to meet their quotas.

Chestnut sweets at a souvenir shop in Akihabara, Tōkyō.

Some sources also mention the close ties between Settan and the imperial court meant chestnut producers might have been familiar with grafting techniques imported from China and used for gardening at the imperial palace. However, the chestnut tree is notably difficult to graft compared to apple and nashi pear trees, so kuri grafting might not have been widespread. This is also why the spread of tanba guri in the Edo period was probably done more with seeds carried by samurai attending the shogun’s court in Edo under the sankin kōtai policy, merchants, and pilgrims than with saplings.

From the Kamakura period to the Edo period: tea ceremony kashi

Entering the Japanese feudal age, chestnuts became an important asset, cultivated not only for consumption but also as a trade good and tax commodity. Chestnut orchards called kuribayashi (栗林) were included with fields and other land assets in various assessment documents of the times.

This period also saw the emergence of the modern Japanese tea ceremony, and various confectioneries called kashi (菓子) were served alongside the tea itself. Documents detailing tea ceremony procedures and reports of tea parties give us a glimpse of the sweets existing at the time.

In addition to chestnuts, popular kashi included kaki (柿) persimmons, mikan, kinkan, yamamomo (山桃) mountain peaches, apples, and uri melons. Chestnut-based kashi were especially popular in autumn and winter. Some recurring chestnut kashi include:

Matcha and kashi. © Photo-AC

15th century

Kurinoko mochi (栗粉餅): grilled and peeled chestnuts passed through a sieve to form a dumpling, eaten warm during the tea ceremony.

16th century

Kuri (栗): no details, possibly steamed and sweetened.

Yaki guri (焼栗): grilled chestnut.

17th century

Kuri dango (栗団子): chestnut flour sweetened and rolled into dumplings.

Mushi guri (蒸栗): steamed chestnut.

Uchi guri (打栗): steamed, ground, and sweetened chestnut, possibly similar to the hira guri from the Heian period. Specialty of the Kōshū region in Kai province.

Recipe books from the 17th century also mention chestnuts being boiled in water or buried in hot ashes for cooking.

Edo period: new varieties across Japan

Following the end of the sengoku jidai civil war, the country was reunified and pacified; internal trade and exchanges resumed with renewed vigor. Chestnut seeds and saplings were spread by travelers, traders, and pilgrims between regions, and local breeds were developed. This variety can be witnessed in early gardening treaties like the Kadan Chikinshō (1695), which includes several entries related to chestnuts:

The kabocha is a common ingredient for tempura, alongside Satsuma imo, shrimps and mushrooms. In that case, it is often thinly sliced before frying, to make sure the flesh is thoroughly cooked. It can also be cooked on a grill, for instance when eating yakiniku. Kinshiuri kabocha form spaghetti-like strands that can be boiled or fried.

Tanba Ōguri (丹波大栗): not a variety per se, but chestnuts from Tanba province are renowned since the Nara period, and they have become synonymous with high-quality chestnuts.

Tanomo guri (頼母栗): chestnut ripening earlier than other varieties. It is ready to be harvested between July and August, compared to Tanba varieties being ripe around September and October.

Hyohyo guri (錘栗): no information, might refer to a small yama guri.

Mitabi guri or sando guri (三度栗): can bear fruits three times a year.

Shidare guri (枝垂栗): low-stooping chestnut.

Hakone guri (箱根栗): no information.

The shidare guri is often associated with the influential Buddhist monk Kūkai, posthumously known as Kōbō Daishi. A legend says kids in a village wanted to grab chestnuts on a tree, but could not reach the high branches. A traveling Kūkai passing by the village would have seen the scene and ordered the tree to lower its branches for the children, giving birth to the first shidare guri. Variations of this story are told in numerous locations across several prefectures. This legend and the stories about the tanba guri certainly seem to indicate chestnuts were especially popular with young children.

The Buddhist monk Kūkai. © Wikimedia Commons

The mitabi guri is mentioned to appear in places where yamayaki (山焼), the seasonal burning of mountains, is practiced. In those regions, each year during springtime controlled fires are lit in mountain woods and meadows to burn weeds and parasitical eggs. Ashes also serve as fertilizer to feed the growth of the remaining plants. Combined with the cutting of firewood in the winter, chestnuts in those areas are left with only stumps from which twigs grow. Chestnut flowers on those twigs can bloom three times in the season (hence the name), or even more depending on the source.

Kuri pressure cooker on mount Takao.

Kuri pressure cooker on mount Takao.

Chestnut wood was also prized as a construction material, especially for its resistance to water. Compared to other construction woods like sugi cedar, hinoki cypress and matsu pine, kuri wasn’t much traded, which is why it was quite expensive in Edo. In response, wealthy daimyō feudal lords cultivated chestnut tree groves in their shimo yashiki, secondary residences in the capital, to save costs on construction projects.

Administrative documents show that landowners of the Edo period started regulating the logging of chestnut trees on their domains to preserve them, proving they were a valuable resource. It is also during the Edo period that kuri tree varieties meant for fruit bearing or logging started to diverge and specialize.

Click HERE to read the second part of this article, where we explore the Japanese chestnut in modern times.