Japanese Food History and Culture

Izakaya: the Japanese Tavern

This is the first part of a two-part series about the Japanese izakaya. In this article, their history and customs are being discussed. The second part is an interview with the owner of Kinjo, an izakaya in the shitamachi (Tōkyō’s old town), to get a rare look behind the counter.

As much a venue for socializing as a pub or tavern, the Japanese izakaya (居酒屋) is an omnipresent part of the country’s landscape. Be it going out with friends, meeting with colleagues after work, getting a quick and cheap lunch or having a drink on the way home, for many Japanese it is the gathering place of choice. From the standing-only hole in the wall to the multistoried complex accommodating full receptions, izakaya come in all shapes and sizes. Today, we’ll take a look at how the modern izakaya came to be and what to expect when going to one.

From the sakaya to the izakaya

Throughout Japanese history, alcohol (酒, sake) was tied to court ceremonies and rituals from the indigenous shintō (神道) religion. Ceremonies where sake was drunk from a shared cup served to reinforce ties between participants, such as a lord and vassal or a village community. Sake is an integral part of offerings to shintō divinities, in this case being referred to as omiki (御神酒), such as in the saying “No god without omiki” (御神酒あらがぬ神はない, omiki araganu kami ha nai).1 Although texts and tales sometimes refer to characters indulging in drinking by themselves, alcohol was an expensive commodity, mostly reserved for special occasions and events.2

Establishments selling alcohol appear in texts going as far back as the Heian period: the Shoku Nihongi (続日本紀, completed in 797) mentions an incident happening at such a shop, then called a shushi (酒肆). However, the modern form of the izakaya wouldn’t appear until the Edo period. Sakaya (酒屋) breweries started appearing around the 13th century and their number continued increasing in the following centuries. Improvements in carpentry and pottery during the Muromachi period allowed production in bigger batches and easier transportation.3 At the onset of the Edo period, commoners were buying sake at those shops and bringing them home for consumption. Sake would be sold by the weight (量り売り, hakari-uri) and poured in a bottle to be returned later to the shop.

Woodblock print of an Edo period sakaya. © Wikimedia Commons

By the middle of the period, regulars of the sakaya would often stay to discuss with the shopkeeper and other customers, sometimes drinking on the spot. Moreover, some shops offered samples to be tasted at the storefront. With time, some shopkeepers would place crates and barrels for people to sit down while drinking. As customers were staying at those shops, they would come to be called izakaya, from the characters i (居, to be / stay) and sakaya.4 In time, tatami mats, cushions, tables and counters would be installed in a more permanent fashion.

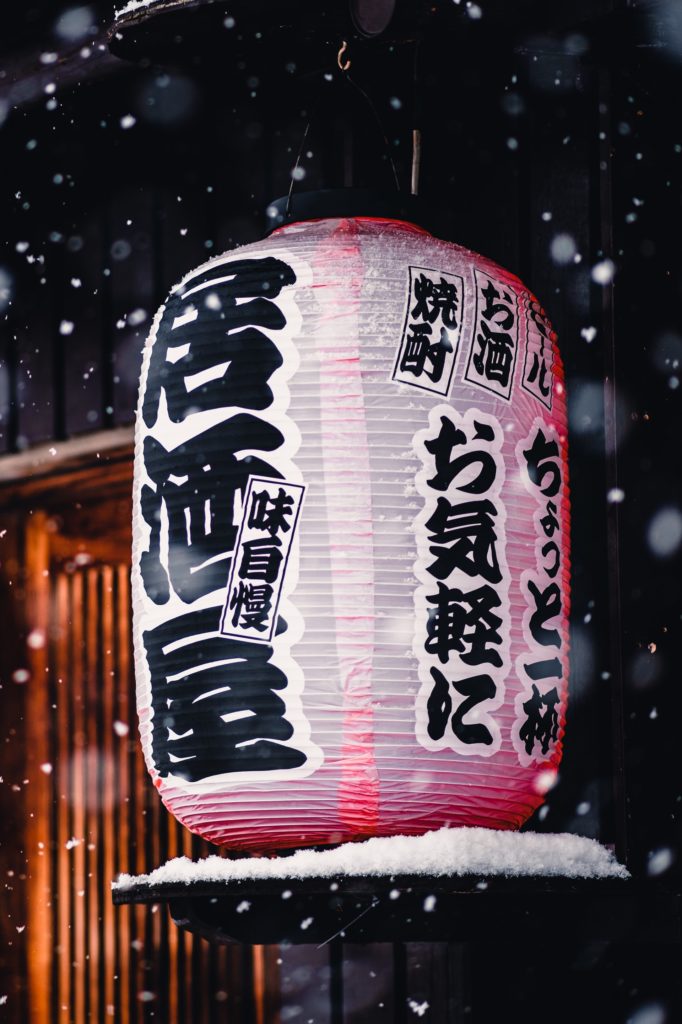

A paper lantern with the “izakaya” characters outside a shop. © Unsplash

Edo workers and side dishes

In the second half of the Edo period, it had become common for workers to gather for drinking and socializing at izakaya after work. One such shop was Toshimaya. Still in activity to this day, it was established on the Kamakura riverbank of the Nihonbashi river in Edo. Due to its proximity to the Edo castle and Kanda neighborhood, this bank was used to unload construction material brought via the waterways, and was surrounded by construction sites and workshops. Frequented by builders and artisans who flocked from the countryside to the capital for work, Toshimaya started offering tōfu dengaku side dishes to eat while drinking. Cheap and filling, the fare enjoyed great success and soon afterwards other izakaya followed suit, offering simple dishes to complement the sake they were serving. With these evolutions, the familiar, current form of the izakaya was born.5

Following the Meiji restoration (1868) and the opening of the country to foreign trade, alcoholic beverages other than the nihonshu (日本酒) rice sake became available. Gyūnabe restaurants started serving beer, at first an imported, exotic drink. As prices decreased, beer was more widely consumed and izakaya started serving them as well, to the point where it is nowadays the most popular menu item.6

After the war: emergence of the franchises

Up until the Taishō era, izakaya were privately owned businesses with a local customer base. After the end of World War II, pushed by a period of economic growth, nationwide izakaya chains started appearing, based on the American model of franchise shops. In the second half of the Shōwa era, several influential and successful companies were operating.

The first shop of the Yōrōnotaki (養老乃瀧) franchise was established in 1956 in Yokohama by a businessman from Nagano prefecture, Yamanda Tomikatsu.7 He expanded on the traditional Japanese model of noren-wake (暖簾分け), whereas the owner of an established shop helps a long-term employee open a branch of the shop, to a system of leasing franchise locations for employees to manage. The brand also focused on serving easily prepared foods and snacks to reduce costs and simplify logistics. By 1973, there were more than a thousand Yōrōnotaki izakaya nationwide.

At the counter of an izakaya.

In 1973, another businessman, Seiji Ishii, founded his izakaya in Sapporo (Hokkaidō prefecture). Named Tsubohachi (つぼ八), it became popular thanks to its low prices and quickly spread across the prefecture, in some places outcompeting the already present Yōrōnotaki branches. The brand eventually spread across Japan, establishing more than 450 locations in 15 years.

Still in 1973, Seimiya Katsuichi opened Murasaki (村さ木) in Setagaya ward (Tōkyō prefecture). Having worked as a part-timer in other izakaya and restaurants, he used his experience to improve the management system and menu of his shops with the goal of keeping costs low and attracting young customers. He notably introduced the concept of “mixed margins” in order to keep a well furnished menu while staying profitable: instead of balancing the price of each individual item against its cost, the price is calculated to keep the menu in its entirety balanced, with more profitable items offsetting the cost of the most expensive ones. The company also expanded on the chūhai (酎ハイ) cocktail, by mixing syrup and sparkling water with shōchū, with the benefits of reducing the price of the drink and making it easier to drink.8

Izakaya franchises in the Heisei era

After the Japanese economy fell into recession in the early 90s, the izakaya boom slowed down, and new business models started emerging. The previous big names gave way to younger chains.

Offshoots of the Tsubohachi chains, such as Monterōza (モンテローザ) and Watami (ワタミ) gained prominence by adapting their offer to the demand of the public, such as expanding towards cocktails, attracting the rising customer base of women entering the workforce. The Korowaido (コロワイド) chain from Kanagawa prefecture instead focused on adopting practices from the family restaurant industry such as central kitchens and distribution centers to optimize the logistics of their locations.9

Customs and etiquette at the izakaya

Izakaya can have a wide variety of interior arrangements depending on the shop. Some small izakaya in narrow alleys can have seats along a counter, while other more spacious places have western style chairs and tables in a wider common area. Private booths for parties can also be available, often with Japanese style low tables and cushions on the floor instead of chairs. Similar to the sakaya of the Edo period, some izakaya called tachinomi (立ち飲み, “drink while standing”) do not offer seats at all, and customers drink and eat while standing around high tables or along a counter. A typical izakaya might offer a combination of those arrangements, with for instance an open space with tables and a counter, and some Japanese style private booths in the back. Compared to Western pubs and taverns, outdoor seating is uncommon, especially in big cities like Tōkyō where streets are narrow and crowded.

After being seated, customers are presented with an oshibori (おしぼり) while they are deciding on their order. It is a wet towel kept cold in the summer and hot in the winter for guests to wash their hands and refresh or warm themselves depending on the season. Once drinks and foods have been ordered, some izakaya will serve an otōshi (お通し), a small appetizer quickly prepared, often a pickled dish. Meant to have a snack to munch on while waiting for the order to come, it also serves as a seat fee, as it will be charged at the end of the evening.

Typically, a menu will include a wide variety of drinks, and snacks that can be quickly prepared and served to accompany them. Items are not ordered all at once, but rather little by little through the course of the evening. During the Edo period, dishes accompanying alcohol were called sakana (肴). Grilled fish was so commonly used however that in modern Japanese, sakana has come to mean fish. Indeed, the kanji for fish 魚 is now read sakana, whereas it was most commonly called uo before.10 Nowadays, side dishes snacked on while drinking are called otsumami (おつまみ).

Once the party is over, all the food and the drinks are accounted for and the bill is typically split evenly among participants. Sometimes, a more senior person, such as the boss in a work related setting, will cover the bill for the whole party. Similarly to the rest of the food industry in Japan, there is no tipping. Another option can be to pay a fee at the start of the evening for a nomihōdai (飲み放題) all you can drink or tabehōdai (食べ放題) all you can eat, often for a set time of 90 to 120 minutes.

Tuna, sea bream and yellowtail sashimi.

Grilled mochi with other side dishes.

Typical foods and drinks

The foods and drinks served in izakaya greatly vary from place to place. For drinks, the most common ones are beers and cocktails such as chūhai (using shōchū) or highballs (using whiskey). Local alcohols can also be found, such as the awamori (泡盛) from Okinawa or umeshu (梅酒) from Wakayama.

Dishes are very varied, and can depend on what is available seasonally. Each dish is served in a single plate or bowl. Serving chopsticks or spoons are then used to transfer the food in smaller plates distributed to each attendant. Typical dishes include various tsukemono pickles, grilled fishes, salads, tamagoyaki, sashimi, salted edamame, kabocha no nimono, yakitori skewers, karaage and cold tōfu topped with katsuobushi. Rice and noodle dishes, such as onigiri, donburi, ochazuke and sōmen are often eaten last, to fill the stomach and signal the end of the evening.

There is also a practice of “bottle keeping” (ボトルキープ, botoru kīpu), where a regular buys an entire bottle of alcohol which is then tagged with their name and kept at the izakaya and can be served to them whenever they come.