Japanese Food History and Culture

Kabocha: Japanese Pumpkins and Squashes

Japanese pumpkins, squashes, and other butternuts, commonly referred to as kabocha (南瓜 or カボチャ) in Japanese, are enjoyed throughout Japan, as illustrated by their myriad varieties and inclusion in numerous local specialties. Part of the famous autumnal triad imo kuri kabocha (芋栗南瓜) with sweet potatoes and chestnuts, they are often associated with cold weather and end-of-year celebrations. In today’s article, we will look at how a Meso-American crop became a staple food in Japan and its evolution and various applications in cuisine.

Origins of the kabocha

The term kabocha, often translated to pumpkin or squash, covers three distinct species. In Japanese, they are denominated as nihon kabocha (ニホンカボチャ, cucurbita moschata), seiyō kabocha (セイヨウカボチャ, cucurbita maxima), and pepo kabocha (ペポカボチャ, cucurbita pepo).

The species that would become known as nihon kabocha (Japanese pumpkin) is thought to have been first cultivated in Meso-America. Seeds have been found at archeological sites in Mexico (5000 BC) and Peru (3000 BC). European explorers probably brought it back to Europe in the 16th century, whereafter it spread all the way to China and Japan. Pumpkins are mentioned in the Chinese pharmacopeia Bencao Gangmu (1578).

At the end of the Edo period, the agronomist Satō Nobuhiro compiled the history and usage of various plants in his Sōmoku Rikubu Kōshuhō (草木六部耕種法). According to Satō, in 1541 a Portuguese vessel drifted ashore in Bungo. They stayed there for several years, and in 1548 obtained from the daimyō Ootomo Sōrin the right to open trade. In return, they offered several presents, including squashes they had brought from the Cambodia province of the Siam kingdom (modern-day Thailand), at the time transcribed Kanbocha by the Japanese. The term “kabocha” would be a deformation of this word.

An alternative theory is suggested in the Nagasaki Yawagusa (長崎夜話草, 1720). Portuguese or Spanish sailors would have brought pumpkin seeds, abobra in their language, to Nagasaki in the second half of the 16th century. The locals understood it as bōbura and started cultivating them in the surrounding area.

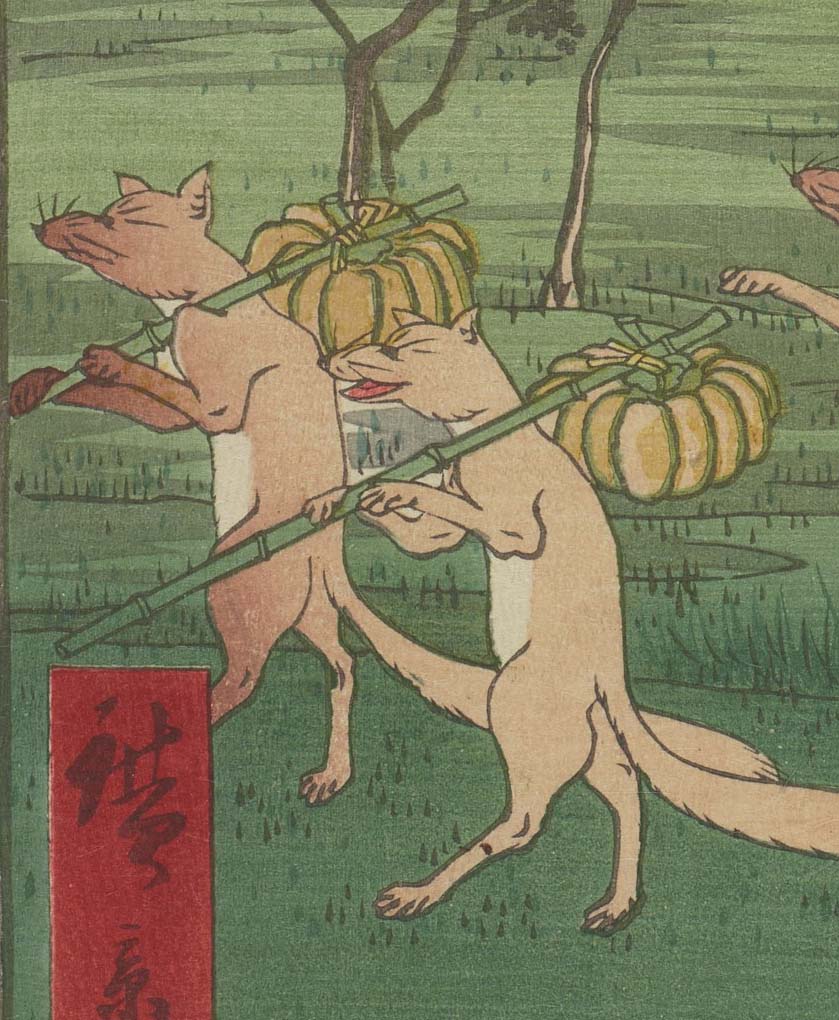

Woodblock print of bipedal foxes carrying pumpkins. (Ota Memorial Museum of Art, via Twitter)

At any rate, by the first half of the 17th century kabocha cultivation was spreading to the whole country, especially in the Tōhoku region. Satō relates that his grandfather brought seeds from Tsukushi province (in northern Kyūshū) to Dewa province in 1620. Still according to him, in 1665 the kikuza kabocha (菊座南瓜, “chrysanthemum kabocha”) variety cultivated in Tsugaru (Mutsu province) was introduced in Kyōto, where the shishigatani kabocha (鹿ヶ谷南瓜 ) variety would develop. Another source, the Yamato Honzō (大和本草), gives 1680 as the start of kabocha cultivation in Kyōto.

Around 1720, pumpkins were still relatively rare, but by 1740 they had become common thanks to their nutritious qualities, ease of cultivation, mild taste, and long shelf life. Kabocha are rich in beta-carotene, vitamins A and C, fibers, and carbohydrates. They can grow in mountainous areas where rice cultivation is difficult. They are harvested in the Summer, but as long as the skin is intact, they can be kept at room temperature until Winter, acting as a complementary staple during the cold months.

A 1921 agricultural survey by the Japanese government found that a lot of indigenous cultivars originate from Aomori and Akita prefectures, lending credence to the narrative of the spread of various breeds from Tōhoku to the rest of the country in the 17th century.

Section of a kuri kabocha.

Seiyō and pepo kabocha

The cucurbita maxima species, called seiyō kabocha (Western kabocha) in Japan, originates from South America. It was brought to Japan from the US in 1863. Suited to cold climates, it became particularly popular in Hokkaidō. Thanks to its sweet taste and nutritional value, it quickly spread in the country; there were six recognized varieties during the Meiji era. The kuri kabocha (栗カボチャ, “chestnut pumpkin”) is its most common variant.

The cucurbita pepo comes from Mexico, where remains in archeological sites from 7000-5000 BC have been found. It is not clear when it was introduced to Japan, but by the Meiji era, 8 varieties were cultivated.

Modern times

Following its introduction in the country, the kabocha steadily spread and the surface allotted to its cultivation increased yearly. The primary species consumed was the nihon kabocha up until the Showa era, when it was joined by the kuri kabocha. F1 hybrids from these two also started to appear, as well seiyō kabocha cultivars more suited to warmer climates.

During WW2, the kabocha was an important crop to increase agricultural output and battle food shortages. Similarly to the Satsuma imo, it was cultivated anywhere space was available, such as gardens and schoolyards. After the war, maybe due to its connection in the collective subconscious with famines and tough times, it quickly lost in popularity; in the 60s, its total cultivated area fell down to one-quarter of its peak in 1944.

Ochazuke topped with grilled kabocha and simmered eggplant.

However, it experienced a revival by the end of the Showa era, with the kuri kabocha becoming the most consumed cultivar. Other varieties also gained traction, such as the closely related zucchini. Pumpkins and squashes are also imported from New Zealand and Mexico.

Nowadays, Hokkaidō prefecture accounts for half the annual kabocha production in Japan.1 However, there doesn’t seem to be a trend regarding consumption per prefecture, and the vegetable is eaten all throughout the country.2

Cultivar and species naming

Kabocha cultivar names and types are not always clearly defined, rendering direct translations difficult. This is compounded by the fact that names in English such as pumpkin, squash, or butternut are likewise ill-defined. Although there are no rigid rules and usage generally depends on the speaker, general trends can be observed.

The term kabocha by itself is often used to denote gourd-shaped nihon kabocha. Bōbura on the other hand tends to be used for spheroid ones.

The kuri kabocha is the most popular squash in Japan nowadays, and by extension, its name is sometimes used to describe all members of the cucurbita maxima species. Another common variant is the happadō from Nagano prefecture.

Confusingly enough, bigger variants of cucurbita pepo are sometimes called seiyō kabocha, although the term actually refers to cucurbita maxima only. Smaller variants can be referred to as kintōga (紅南瓜). Common pepo kabocha cultivars include the string-like kinshiuri (金糸瓜) spaghetti squash, sometimes called sōmen kabocha (素麵カボチャ), as well as the ponkin kabocha (ポンキンカボチャ) and omocha kabocha (おもちゃカボチャ) used as decorations or fodder.

Recipes and dishes

The quintessential Japanese kabocha dish is the kabocha no nimono (カボチャの煮物). The vegetable is cut into single-bite pieces and slowly simmered in a soy sauce broth until completely soft. It is a warm, filling, and easy-to-cook dish made with readily available ingredients, so it comes as no surprise that it is a very popular fare in Japan. It can often be found in bentos or on izakaya menus.

The kabocha is a common ingredient for tempura, alongside Satsuma imo, shrimps and mushrooms. In that case, it is often thinly sliced before frying, to make sure the flesh is thoroughly cooked. It can also be cooked on a grill, for instance when eating yakiniku. Kinshiuri kabocha form spaghetti-like strands that can be boiled or fried.

Kabocha no nimono (simmered pumpkin).

Kabocha as a flavor for sweets is popular, especially during Autumn. There are kabocha flavored baumkuchen, wagashi or amazake, amongst others. Kabocha is often used as a filling, for instance in kabocha montblanc (instead of chestnut) or kabocha manjū. Kabocha ice creams can often be found in supermarkets and convenience stores.

Its versatility means it can also be used for Western-style dishes such as potages with melted cheese, pumpkin mayonnaise salads, or pumpkin pies.

Kabocha potage served in a hollowed-out kabocha.

Soy milk soba noodles with grilled kabocha and other toppings.

Local specialties

Owing to its popularity, various local dishes based on the kabocha can be found throughout Japan.

During the Winter solstice in Ibaraki prefecture, kabocha no itokoni (かぼちゃのいとこ煮) is eaten. The kabocha is slowly simmered with adzuki red beans, thought to bring luck and ward off evil spirits. Other vegetables can also be added. The dish may have originated from vegetables used as offerings during New Year’s Eve being cooked after the celebrations.3

In Nagano prefecture, roasted dumplings made from fermented buckwheat dough called oyaki (お焼き) are especially popular with kabocha filling.

For hōtō (ほうとう), Yamanashi prefecture’s signature nabe hotpot dish, kabocha is mixed with large, flat udon noodles and other vegetables.

In Ōita prefecture, the birthplace of the Japanese kabocha, some variations of the local soup called koneri (こねり) include kabocha.

The historical part of this article has been mostly based on research compiled in the book Nihon no Yasai Bunkashi Jiten (日本の野菜文化史事典) by Aoba Takashi. Other sources are referred to as usual.