Japanese Food History and Culture

Kuri: the Japanese Chestnut – Part 2

This is the second part of a two-part article about the Japanese chestnut. In the first one, the cultivation of the kuri from prehistoric times up to the Meiji period was covered. The second part discusses the modern cultivation and consumption of the chestnut. Unless stated otherwise, the information shared in this article is based on the research compiled in the book Kuri – Mono to Ningen no Bunkashi (栗・ものと人間の文化史) by Imai Keijun. Other sources will be referred to as usual.

Kuri in the 20th century

With the spread of the kuri across the entire country, a plethora of local varieties appeared during the Edo and Meiji period. This proliferation led to confusion, as some names were used for different breeds and some cultivars might have several names depending on the producer. This in turn led to producers, researchers, and businessmen forming associations to regulate kuri production. Those associations also facilitated research and promotion of the kuri, bringing about a national surge in chestnut consumption.

The onset of WW2 slowed down production and research, but they seemed poised to take off again after the end of the war. However, a new menace on the Japanese chestnut had appeared.

In 1941, a new species of wasp, dubbed kuritama bachi (oriental chestnut gall wasp, dryocosmus kuriphilus), was spotted in Okayama prefecture. This parasitic insect, possibly introduced from China, lays its eggs on chestnut sprouts, forming galls when they hatch in the summer. This in turn hinders the growth of new leaves, and the tree ends up withering or even dying. The wasp is resistant to common insecticides like DDT, and affects both cultivated and wild chestnut trees. By 1955, it had spread to the entirety of Japan and was inflicting severe damage to plantations.

In response, cultivars resistant to the wasp were quickly selected, but by the time they were widely used, the damage had been done. Out of the 150 to 200 kuri varieties cultivated before the epidemic, less than 20 were left. The varieties cultivated today are all resistant breeds.

A yakiguri stand in Iwamotochō station, Tōkyō.

What is more, in the 60s, resistant breeds started to show signs of infection as well, meaning a new strain of chestnut wasps was affecting those kuri species thought to be more less vulnerable. In response, in 1982 producers started to release in their orchards another Chinese wasp, the onaga kobachi (torymus sinensis). This parasitoid wasp is a natural enemy of the chestnut wasp and helped prevent further destruction of chestnut trees, both wild and cultivated.

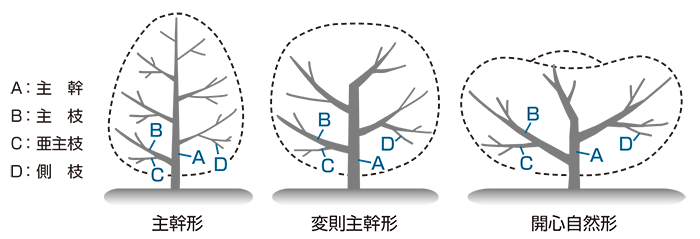

Compact-shaped cultivation and production

Taking inspiration from pioneering works with apple trees, chestnut producers adapted a cultivation method named teijudaka saibai (低樹高栽培), or compact-shaped cultivation. High branches of trees are cut in order to keep them under four meters tall, growing horizontally instead. Thanks to a more even repartition of sunlight between high and low branches, trees grown this way yield bigger and more numerous fruits, and are more resistant to typhoons and strong winds. Moreover, trees not exceeding four meters in height mean a single worker with a ladder can easily access the entire tree, simplifying work in the orchards. It would also seem that compact-shaped chestnut trees are more resistant to chestnut wasps: some plantations that adopted compact-shaped cultivation early on never had to use onaga kobachi to counter them. Further experimentations led to the development of a more advanced, “super compact-shaped cultivation” method.

Illustration of the effect of compact-shaped cultivation on trees. © ja-sc.or.jp

From the end of the Meiji period, domestic chestnut production was steadily increasing until it experienced a sharp decline during WW2. After the end of the war, it started to increase again, but by then, the spread of the kuritama bachi severely slowed down progress. Nonetheless, production peaked in the 70s and 80s thanks to resistant cultivars. Currently, the most common breeds are tsukuba (筑波), tanzawa (丹沢), ginyose (銀寄) and ganne (岸根).

However, kuri production has been in a slow decline since then due to the competition from imports, notably from Chinese and Korean chestnuts. In 2006, domestic production levels were lower than in 1955.

Amaguri: chestnuts from China and Korea

Since the early 20th century, Chinese sweet chestnuts from Heibei province have been popular in Japan, where they are called tenshin amaguri (天津甘栗, “Tianjin sweet chestnut”, from the name of a major trading port in China1) or just amaguri. In addition to those small chestnuts easier to peel than their Japanese counterparts, Chinese immigrants also brought a new way of cooking them. Yakiguri, kuri cooked in an iron pot with sand and seasoned with sesame oil and sugar, was already a common fixture at shops and festival stalls. But at Kanemasuya, a shop opened in the Asakusa neighborhood of Tōkyō by young Chinese immigrants in 1910, they first cooked sugar with small, black pebbles before grilling amaguri with those caramel-coated pebbles. This method allows for the chestnuts to be evenly cooked and the sugar to penetrate their flesh.

Thanks to its sweet, mild taste and ease of peel, the tenshin amaguri quickly spread to the whole country. Together with the Korean heijō guri (平壌栗), those chestnuts were sometimes referred to as shina guri (支那栗).

Kuri dishes and specialties

In Japan nowadays, chestnuts are used in cooking, for desserts, as a flavoring, or eaten as is. Several local specialties also use kuri, and they are a staple of osechi ryōri (お節料理), traditional New Year’s dishes. It is most popular in the colder months of the year, and is part of the imo kuri kabocha (芋栗南瓜) autumnal triad.

Yakiguri, kuri kinton and montblanc.

Muki amaguri (むき甘栗, “peeled sweet chestnut”) can be commonly found all year round in supermarkets and convenience stores. Yakiguri stands can be seen in train stations or in department stores, and are especially popular in the winter. Hidaka town, in Saitama prefecture, is known for its kuri no shibukawa ni (栗の渋皮煮): the outer skin is peeled and the chestnut is then slowly simmered with sugar until soft. It is then eaten with the astringent skin.2

Muki amaguri bags in a supermarket in Shimo Kitazawa, Tōkyō.

When used for cooking, the most common dish is kuri gohan (栗ご飯), where tanba chestnuts are cooked with a mix of white and glutinous rice. It is particularly popular in Kyōto prefecture.3 In kuri okowa (栗おこわ), common at autumn festivals and celebrations in Saga prefecture, chestnuts are steamed with glutinous rice and adzuki beans. It is also used for offerings at shrines.4 In Nagasaki prefecture, vegetables are simmered with chestnuts to make kuri tsubo (くりつぼ).5

Taiyaki filled with kuri cream in Shimo Takaido, Tōkyō.

Probably the most popular chestnut dish in Japan, the montblanc, or monburan (モンブラン), is a pastry made with chestnut purée in a vermicelli shape. In fact, the dish is so popular that other flavors can be found, such as Satsuma imo, kabocha, strawberry, matcha tea, and more. Kuri chestnuts are also used in other yōgashi Western sweets such as baumkuchen. They can be found as fillings in wagashi such as daifuku, dorayaki, manjū, yōkan, and taiyaki, or used for flavor in sweet drinks like amazake.

Example of montblanc. 1st step: meringue.

Example of montblanc. 2nd step: whipped cream.

Example of montblanc. 3rd step: kuri vermicelli.

They are simmered in sugar and mixed with mashed Satsuma imo to make kuri kinton (栗きんとん), a staple of New Year’s osechi ryōri. The golden hue of the dish symbolizes wealth, and it is eaten to bring prosperity and fortune for the year to come. A variation from Gifu prefecture, made with steamed and then boiled chestnuts is eaten throughout the year.6

Chestnuts are also used for making alcohol, such as kuri shōchū. Recently, Japanese distilleries have been experimenting with kuri wood casks to produce kuri-aged whisky.7

Click HERE to read the first part of this article, where we explore the history of the Japanese chestnut.